Interviews

A Different Way of Thinking

Can classic German design values like durability, reliability, functionality and a systematic approach be transferred to digital product design? Does nationality actually still play any role at all in the digital arena? Martin Krautter discusses these and other questions with Christian Hanke, Creative Director at Edenspiekermann, and Philipp Thesen, Head of Design at Deutsche Telekom.

Can classic German design values like durability, reliability, functionality and a systematic approach be transferred to digital product design? Does nationality actually still play any role at all in the digital arena? Martin Krautter discusses these and other questions with Christian Hanke, creative director at Edenspiekermann, and Philipp Thesen, head of design at Deutsche Telekom.

I think everybody has an idea of what German product design is. You immediately think of classic brands like Braun or BMW. We’re here at a company that mainly offers services. Philipp, are Telekom’s products actually even perceived as German in other countries?

Philipp Thesen: It varies a lot. Internationally speaking, people have very positive associations with German design. Several years ago when we were defining the design language of the Telekom products and our entire digital experience, the question came up as to whether there are any specifically German aspects. Our company sells its products in 30 countries, but on the other hand our German origins are part of our brand identity. I’ve always been interested in German design and I have to admit that, for a long time, I thought the kind of functionalism that came out of the Ulm School of Design was the global norm. But studying abroad made me realise that isn’t the case everywhere. There are certain things international designers value as German attributes: a fundamentally systematic approach, a sustainability mindset and an aspiration to quality that isn’t seen as luxury. But because of the Ulm School of Design’s international influence, there’s definitely something universal about those things too.

Christian Hanke: When we opened our Los Angeles office in 2015, the fact that we’re a European agency, or more specifically a German one, was an important sales argument – like a quality label. Our founder Erik Spiekermann, who represents precisely those classic attributes, is very wellknown over there, and that was a big help. Thesen: On the other hand there are plenty of high-profile designers from Germany who disappear behind their work; that’s not the case in a country like Italy or France.

Hanke: Do you think that’s typically German?

Thesen: I don’t know, but I studied in Milan and Helsinki. In Italy, designers like to foster a personality cult to some extent. And although people in Scandinavia tend to keep a very low profile, designer branding plays a more important role than it does here. Both those countries have strong design companies with artisanal roots. In Germany, design is more likely to have its breeding grounds in industry, and chief design officers like Gorden Wagener of Mercedes-Benz have only recently started to have a public presence. Even so, German designers are often still invisible ghosts: the things they create are enjoyed by people all over the world, but their authorship tends to remain a mystery.

Philipp, how have the design qualities that you identified as typically German been translated into Telekom’s digital products? Can that kind of thing be expressed in a concrete way?

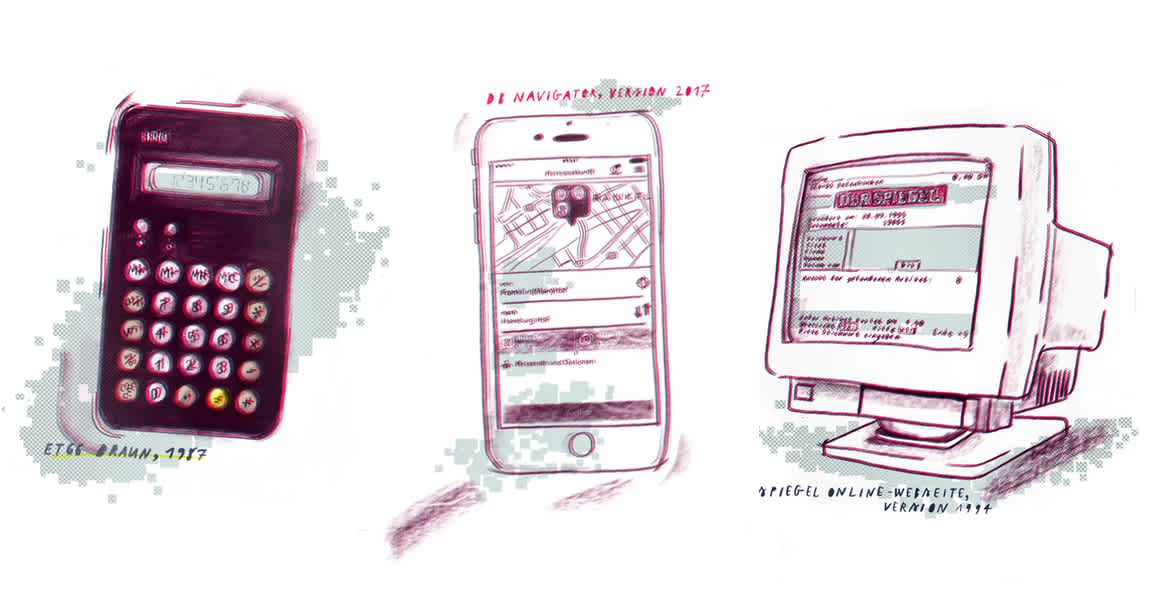

Thesen: We took a very functional approach right from the outset. The realisation that the digital experience mainly concerns innovations in hardware, software and services has only really caught on over the last few years – it’s important to remember that. Prior to that, “digital” mainly meant websites and apps, it was all about entertainment. And the functional aspect was often merely expressed in the form of functionalistic references, like the interfaces of the early Apple products: although their style was reminiscent of Dieter Rams, they weren’t designed in the same spirit at all.

The calculator by Dietrich Lubs is the classic example: its look was simply copied ... Surely that’s got something to do with the fact that digital products are inherently less tangible than hardware products, wouldn’t you say?

Hanke: Do you really think so? I think it’s just that it took us a few years to learn what a digital look and feel is. We designers were still pretty clumsy to start with. It took time to understand just how important things like transitions and performance or language and tonality really are for a digital product experience.

Thesen: That’s exactly what I mean. The tendency to reference earlier designs resulted from a certain degree of helplessness.

Hanke: Or to put it another way, from the necessity to get the user to make the connection. That’s how icons like the floppy disk as a symbol for “save” came about, or the use of imitation leather in the calendar app for that matter. None of that’s necessary anymore and we can be more mature in how we design, thank God!

Thesen: The digital sphere is a totally new realm of experience – in a literal sense too. It’s no coincidence that most digital applications tended to be created by industrial designers to start with. Ten years ago, we mainly employed industrial designers too: they think more three-dimensionally, which enables them to negotiate navigation structures better. Graphic designers found that difficult to start with; they concentrated more on the interface.

To some extent, the importance of design classics can be attributed to insecurity too: when consumers aren’t sure what’s good, they tend to fall back on classics. Does that apply to the digital sphere too? Can tried-and-tested designs become classics?

Hanke: No, it’s a different way of thinking. Obviously there are metaphors or a certain aesthetic that reflect the corresponding zeitgeist. Take Wikipedia, for instance: on the whole, it will probably stay just the way it is for ever. But does that make it a design classic? Or do sites like that belong in the museum?

Thesen: No – with the possible exception of Spiegel Online’s first news site! (Laughter) But that’s precisely the point: digitality fundamentally changes a designer’s relationship to their work and, by extension, their self-image. For a long time, designers dreamed of creating things that would end up in the museum and outlive them as icons for posterity. That’s simply not possible in the case of products that are relaunched what feels like 600 times a day on the basis of user research and iteration. Which isn’t to say that certain digital applications don’t deserve to be considered outstanding in the context of their time.

Hanke: The first iPhone OS is one such time capsule!

Thesen: Yes, or important paradigm shifts like Apple’s Lisa – the birth of the graphical user interface! But nobody would want to fall back on that kind of thing just because they feel insecure – it’s not the same as buying an Eames Chair because you can’t go wrong with it. Perhaps digital design will follow in the footsteps of the invisible industrial designer.

Hanke: I think it’s slightly different in digital editorial design because it’s OK to be more expressive when there’s a narrative involved. But it’s nonsense to talk about something like “experimental navigation” in connection with digital products. It’s the kind of thing you might read in an undergraduate dissertation, but otherwise you can’t help wondering whether there’s actually a niche for it! (Laughter)

Well then, would you say there are certain design principles that have acquired classic-like status in the digital sphere?

Hanke: Yes, definitely. There are some very powerful conventions. I realise that when my kids try to swipe printed pictures away with their index finger or build the hotword for activating Alexa into their jokes. The swipe gesture was created for the Palm OS and, in the form of “swipe to unlock”, was even considered a brand-defining pattern for iOS – until a new technology came along and Apple users got out of the habit. That’s how the native platforms, successful products and major design systems like Google’s Material Design manage to keep playing such an influential role in digital design.

Thesen: And that will continue, lots of new things will emerge. There’ll be new forms of interaction that will become increasingly important for the user experience, things like language, gestures, predictive interfaces. And classics will establish themselves in those areas too.

In such a fast-moving field as this, can you imagine anybody nailing 10 theses to the door the same way Dieter Rams did when he defined good design in 10 principles?

Hanke: But those principles don’t actually refer to a specific area of design!

Thesen: They’re more about a professional ethos, an attitude.

Hanke: And a lot of things about them are very German. Before we met today, I asked a few non-German colleagues about their idea of German design in the hope of getting some answers that go beyond the usual clichés.

Thesen: Although clichés are actually only condensed information ...

Hanke (laughs): Precisely! According to a colleague from Slovenia, Germanness is scheduled fun. But in a good way! Another colleague said being an artist and engineer rolled into one is a typically German trait. One of our agency’s guiding principles expresses a similar sentiment: we want to make things that are important, useful and attractive – but never just useful and never just attractive.

Christian Hanke and Phillipp Thesen illustrated by Anni von Bergen

But even so, the design processes involved in creating a digital product or service aren’t the same as in an area like classic product design. A chair doesn’t get updated six months down the line; it’s a finalised product.

Thesen: But it could be a different story if you think about the possibilities of technologies like 3D printing. Digitisation is making the product world more complex and more individual. That’s why the whole topic of design methods and processes, which is rooted in the technology boom of the 1960s, is so topical again right now.

Hanke: When we’re comparing print and online journalism, we talk about finite and infinite products. Print journalists think in terms of deadlines, whereas for their online colleagues the real work actually only starts after publication – when other people get involved and want to have their say, or when a news situation changes or a story develops. That calls for a totally different kind of design.

Working in such an open-ended way requires a drastic change of thinking on the part of product designers.

Thesen: It’s a question of the motivation that drives their work. There are explorative designers who want to unlock the world and others who want to define what the world should be like. Those are the two archetypes I keep running into, anyway. (Laughter)

A kind of “I know what’s good for you” attitude is another thing that’s often considered typically German. How does that play out in UX design?

Hanke: Authoritarian design? It doesn’t work in that context, or it’s simply seen as bad design.

Thesen: In UX design, the focus is on the user. Designers are more like moderators between the real world and the technology. You don’t get far with an authoritarian approach.

But when it comes to service design, Germany is considered something of a late developer – how does that fit in with what you’ve been saying?

Thesen: I don’t see Germany as a service wilderness at all. I know quite a few people in other parts of Europe who use the Deutsche Bahn app to look for train connections in their own country – simply because it’s so reliable. And there are plenty of other examples of excellent service design from Germany.

Hanke: I think that perception has a lot to do with the very German need to criticise everything. Whenever we change a digital product with lots of German users, their first reaction is always to complain. But it’s often a very different story in countries like Switzerland or the US.

Thesen: Calling Germany a service wilderness is a habit that dates from the 1990s.

Hanke: The term’s got a lot to do with the civil-service-like structures that were common back then. A lot of companies had monopolies and didn’t have to vie with competitors the way they do nowadays. It’s much more interesting to ask what we can learn from that attitude. Are there any conclusions that can be drawn? Does the feedback help improve your offerings? Companies could change a lot of things for the better just by being more consistent about involving the people who are in contact with their product users in the development processes. Participation is vital: if we took to designing things with people instead of over their heads, we could lay the idea of Germany being a service wilderness to rest.

Thesen: The design discipline needs to play a much bigger role when it comes to mediating between humans, technology and business interests. That means taking an interdisciplinary stance and having a prolific, multifaceted cultural knowledge. But the German perspective soon turns out to have a pretty limited horizon.

Let’s talk about design thinking: how compatible is its methodology with German corporate cultures?

Hanke: We’ve had very different experiences across various sectors and markets. I once had a kind of eureka moment when somebody reminded me of Maslow and his hierarchy of needs in this context. Self-actualisation only comesat the very tip of the pyramid. That means as long as people’s “deficiency needs” aren’t met, as long as they don’t know how safe their job is or what role they play within the organisation, or if they’ve never experienced what it feels like to achieve something together with their colleagues, they won’t be able to give any thought to innovations. Then there’s absolutely no point in holding innovation workshops and handing out colourful post-its for people to scribble their ideas on. It just won’t work.

Fair enough, but that’s not a specifically German problem. Or is it perhaps a problem for the SME sector, which is particularly strong in Germany?

Thesen: It’s more a question of how professionally a company approaches the topic of innovation and how influential design is within an organisation. It’s essential to realise that this kind of work costs a lot of money and takes a lot of energy. Thinking about design and innovations isn’t a hobby; nobody in the company does it as a sideline.

Do you think Germany’s SME sector needs to become more digital?

Hanke: Yes and no. Everybody has to make their own mind up as to where their future business areas lie and what role they want digitalisation to play – resorting to action for action’s sake just because you’re worried doesn’t amount to a concept. In my opinion, the biggest challenge is having to think in terms of two operating systems at the same time, because no company can afford to suddenly only pursue digital avenues from one moment to the next. It’s important to seek, develop and test new business models parallel to one another, as well as to create the necessary cultural prerequisites within the corporate culture.

Thesen: Innovations can’t be introduced overnight either. For a company like Telekom, it’s a huge risk to suddenly redesign IT structures or experiment with business models and tariffs. The sums of money involved can easily go into the billions. That’s a fundamental problem when you’re dealing with big structures, but it’s one that has to be solved in the long term. The only answer to disruptive business models like Uber and the like is to come up with compelling products and services yourself.

Are there any internationally successful digital products that are perceived as German?

Thesen: When apps or other digital products are successfulit doesn’t matter whether they come from Tel Aviv, Mountain View or Berlin. In the 1990s, which saw the first phase of design management’s professionalisation in Europe, cultural differences in product design were a major issue. Back then the US did a lot of designing for the European market, and they wanted to make sure they stayed on the consumer’s wavelength. That way of thinking has become totally outdated. Nowadays, nations are dissolving in cyberspace. Consumer preferences all over the globe are becoming more and more similar – and that applies to digital products too. At the same time, digitality permits a huge variety of highly customised interfaces and user experiences.

Hanke: At the very most, people have different habits. You have to adapt the topics and content, but not the product structures. Take Red Bull’s rollout of global digital products in 60 markets, for instance, which focused more on contexts and usage occasions than on differences between countries. And quite apart from the directions people read and swipe in, language is an issue too, of course: Swisscom has a special Swiss German voice control app for TV because Siri and Cortana don’t work in Switzerland – they can’t decipher the Swiss dialect. Otherwise, it’s not so much the country you’re designing for that’s interesting as the attitude you adopt. My favourite comment on our relaunch for online newspaper NZZ.ch was this: It’s the epitome of Swiss precision! Made in Germany ...

Thesen: You’re right, at the end of the day it’s only your attitude that matters – and in Germany it just happens to be the case that our attitude has been influenced by the Ulm School of Design.

Hanke: It would be interesting to see what Ulm Plus looks like. I once read something really fascinating about German designer and art director Willy Fleckhaus – somebody who’s always played an incredibly important role for me. Apparently, he learned his sense of order from Max Bill and his great sense of imagination from America’s Alexey Brodovitch, the Russian-born art director of Harper’s Bazaar. That’s what I’d like to see in future: it would be wonderful if we could combine our methodical instincts with imagination.

Originally published in designreport

Illustrations: Anni von Bergen